Dr. Julia Gallo sat on a dusty carpet and eyed the cracked mud bricks and exposed timbers of the tiny room. She didn’t need to look at her interpreter to know that he was watching her. “Ask again,” she said.

Sayed cleared his throat, but the question wouldn’t come. They were in dangerous territory. It was bad enough that the young American doctor dragged him to the most godforsaken villages in the middle of nowhere, but now she was openly trying to get them killed. If the Taliban knew what she was doing, they’d both be dead.

The five-foot-six Afghan with deep brown eyes and black hair had a wife, three children, and not so insignificant extended family that relied on him and the living he made as an interpreter.

For the first time in his twenty-two-year-old life, Sayed had something very few Afghans ever possessed—hope; hope for himself, hope for his family, and hope for the future of his county. And while what he did was dangerous, there was no need to make it any more so by taunting the specter of death. Dr. Gallo, on the other hand, seemed to have a remarkably different set of priorities.

At five foot ten, Julia was a tall woman by most standards, but by Afghan standards she was a giant. And although she kept her long red hair covered beneath an Afghan headscarf known as a hijab, she couldn’t hide her remarkable green eyes and the fact that she was a very attractive woman. She was a graduate of the Obstetrics & Gynecology program at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and ten years her translator’s senior. And while she may have shared Sayed’s vision for the future of Afghanistan, she had her own opinions of how best to bring it about.

In a country where most parents didn’t name their children until their fifth birthday because infant mortality rates were so high, Dr. Gallo and others like her had made a huge difference. Infant mortality was down more than eighteen percent since the Taliban had been ousted. That meant forty to fifty thousand infants who would have died under the old regime were surviving. She should have been thrilled, but for some reason she wasn’t. She was unhappy and that made her push harder to bring about change.

Gallo knew she wasn’t just rocking the cultural boat on these visits out into the countryside, she was shooting holes in the stern and reloading, but she didn’t care. The Taliban were a bunch of vile, misogynistic bastards who could rot in hell as far as she was concerned.

“Ask her again,” she demanded.

Sayed knew the answer and was certain Dr. Gallo did, too. It was embarrassing for the women to have to answer, yet she pressed her point anyway. It was the setup for a message she had taken to proselytizing on a regular basis. Gallo had become a zealot in her own right, no different from the Taliban, and as much as Sayed respected her, this was going to be their last trip out of Kabul together. He would respectfully ask their NGO, CARE International, not to assign him to her anymore. No matter how nice she had been, it didn’t mean he had to die because of her.

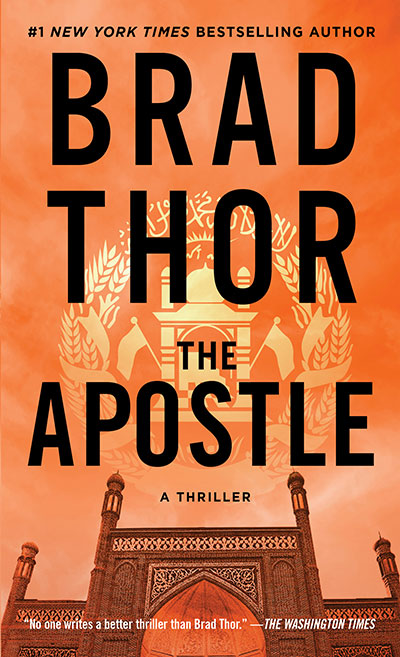

Continue reading The Apostle excerpt.